Blockchain meets Internet Routing

We study the effects of the Internet, especially with respect to routing on public Blockchains, taking Bitcoin as our use case. To that end, we first uncover the impact that Internet routing attacks (such as BGP hijacks) and malicious Internet Service Providers (ISP) can have on Bitcoin (see paper). Next, we provide a concrete relay design that guarantees connectivity to the Bitcoin network even in the presence of a malicious ISP (see paper). Both our attacks and our relay design generalize to other public Blockchains.

Attacks

Because of the extreme efficiency of Internet routing attacks and the centralization of the Bitcoin network in few networks worldwide, we show that the following two attacks are practically possible today:

Partition attack: Any ISP can partition the Bitcoin network by hijacking few IP prefixes.

Delay attack: Any ISP carrying traffic from and/or to a Bitcoin node can delay its block propagation by 20 minutes while staying completely under the radar.

The potential damage to Bitcoin is worrying. Among others, these attacks could reduce miner's revenue and render the network much more susceptible to double spending. These attacks could also prevent merchants, exchanges and other large entities that hold bitcoins from performing transactions.

Defences

To secure Bitcoin against the most effective attack, namely the partition attack we build SABRE. SABRE is a secure and scalable Bitcoin relay network which relays blocks worldwide through a set of connections that are resilient to routing attacks. SABRE runs alongside the existing peer-to-peer network and is easily deployable. As a critical system, SABRE design is highly resilient and can efficiently handle high bandwidth loads, including Denial of Service attacks. Our results demonstrate that SABRE is effective at securing Bitcoin against routing attacks, even with deployments of as few as 6 nodes.

We built SABRE by levaraging two key technical insights.

BGP Policies: We leverage fundamental properties of inter-domain routing (BGP) policies to host relay nodes: (i) in networks that are inherently protected against routing attacks; and (ii) on paths that are economically-preferred by the majority of Bitcoin clients. These properties are generic and can be used to protect other Blockchain-based systems.Programmable switches: We leverage the fact that relaying blocks is communication-heavy, not computation-heavy. This enables us to offload most of the relay operations to programmable network hardware (using the P4 programming language). Thanks to this hardware/software co-design, SABRE nodes operate seamlessly under high load while mitigating the effects of malicious clients.

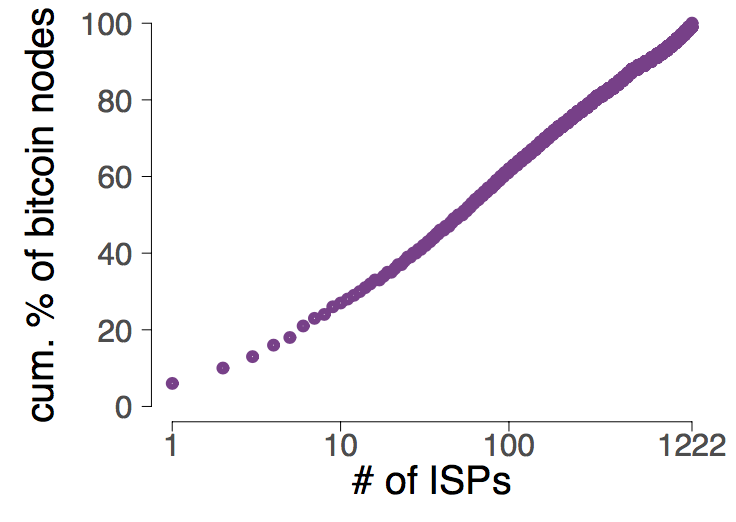

Bitcoin hosting centralization makes it vulnerable to routing attacks

Although one can run a Bitcoin node anywhere on earth, the nodes that compose the network today are far from being spread uniformly around the globe.

Particularity, our results indicate that most of the Bitcoin nodes are hosted in few Internet Service providers (ISPs): 13 ISPs (0.026% of all ISPs) host 30% of the entire Bitcoin network (left graph).

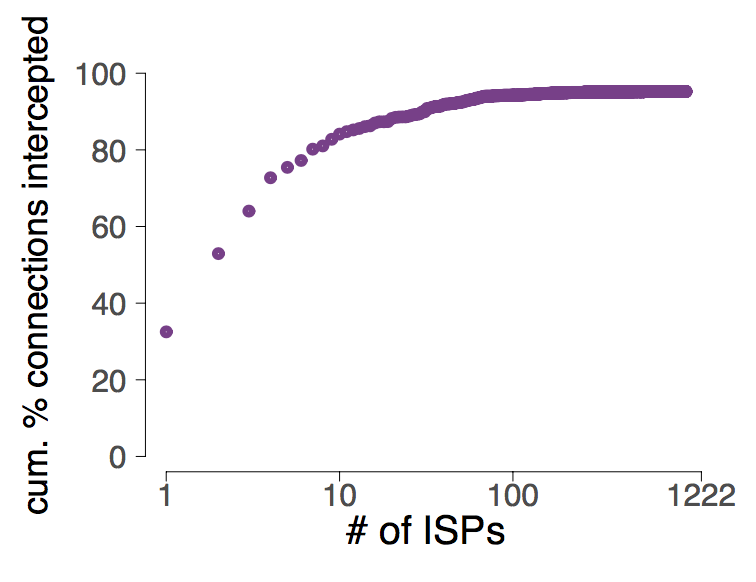

Moreover, most of the traffic exchanged between Bitcoin nodes traverse few ISPs. Indeed, our results indicate that 60% of all possible Bitcoin connections cross 3 ISPs. In other words, 3 ISPs can see 60% of all Bitcoin traffic (right graph).

Together, these two characteristics make it relatively easy for a malicious ISP to intercept a lot of Bitcoin traffic.

Cumulative fraction of Bitcoin nodes as a function of the number of hosting ISPs (left). Cumulative fraction of all possible Bitcoin connections as a function of the number of ISPs that intercept them (right). Data was collected from 5 November 2015 to 15 November 2016.

Routing attacks are pervasive and do divert Bitcoin traffic

A BGP hijack is a routing attack in which an ISP diverts Internet traffic by advertising fake announcements in the Internet routing system.

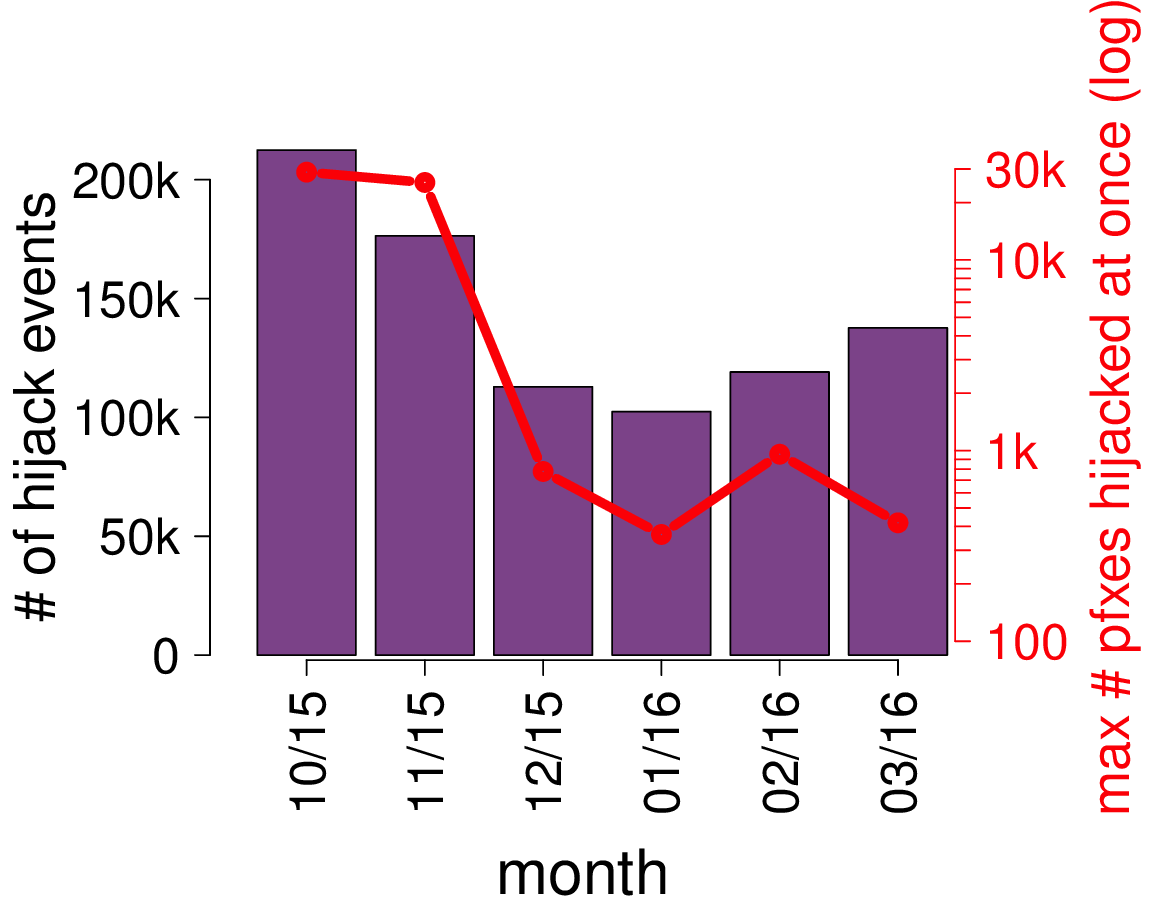

Such attacks are frequent. Actually, our results indicate that up to hundreds of thousands of hijacks happen each month. Some of those events also affect a huge number of Internet destination: up to 30,000 IP prefixes (left graph).

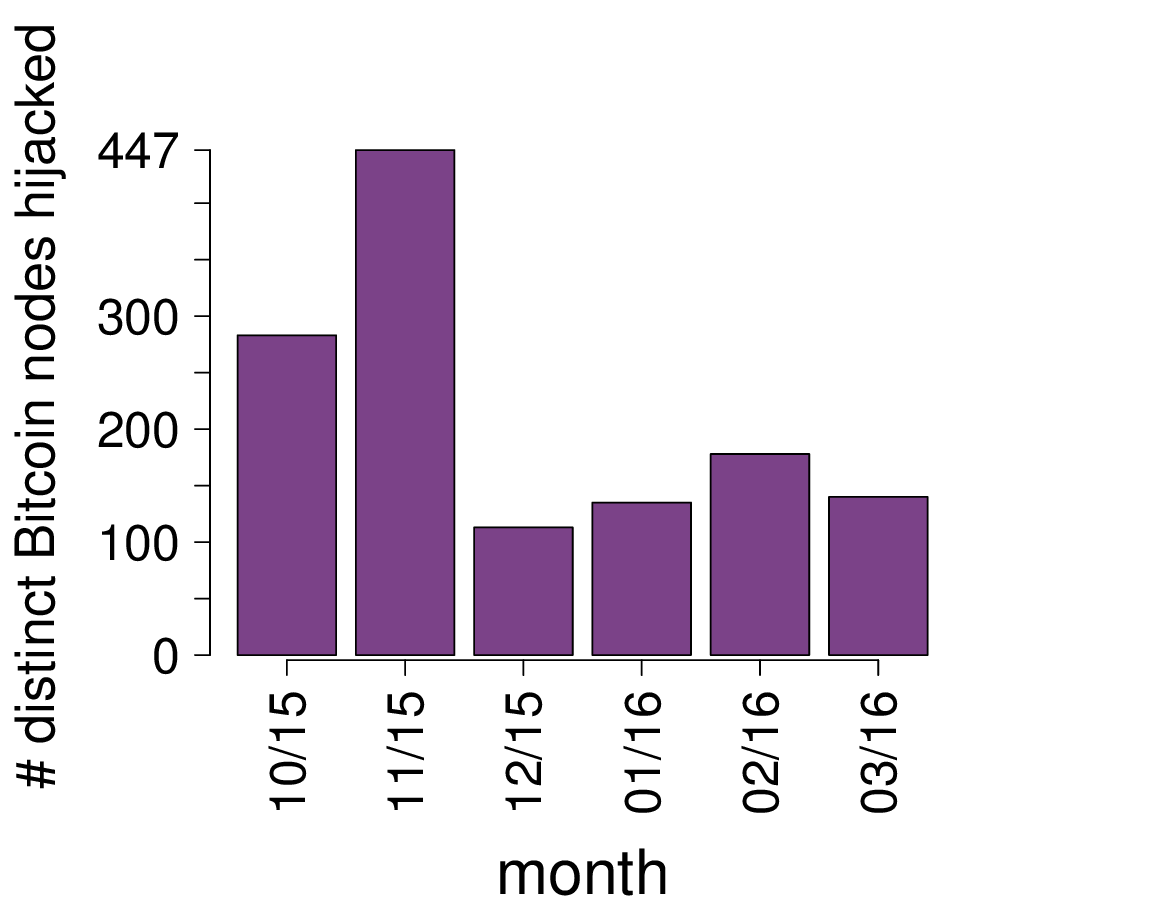

These attacks already affect the Bitcoin network, today. Indeed, we found that, each month, at least 100 Bitcoin nodes are the victims of BGP hijacks, while 447 distinct nodes (∼8% of the Bitcoin nodes) ended up hijacked in November 2015 (right graph).

Number of bitcoin clients whose traffic is diverted by BGP hijacks per month (left). Number of hijack events per month (right). Data was collected from October 2015 to March 2016.

Attack#1: Routing attacks can partition Bitcoin into pieces

An attacker can use routing attacks to partition the network into two (or more) disjoint components. By preventing nodes within a component to communicate with nodes outside of it, the attacker forces the creation of parallel blockchains. After the attack stops, all blocks mined within the smaller component will be discarded together with all included transactions and the miners revenue.

Attack scenario:

- Step 0: Nodes of the left and the right side of the network communicate via Bitcoin connections denoted by blue lines.

- Step 1: The attacker wishes to split the network into two disjoint components: one on the left hand-side and one on the right hand-side.

- Step 2: The attacker attracts the traffic destined to the left nodes by performing a BGP hijack.

- Step 3: Soon after the hijack, all traffic sent from the right to the left side is forwarded through the attacker (red lines).

- Step 4: The attacker cuts these connections, effectively partitioning the network into two pieces.

- Step 5: During the attack, nodes within each side continue communicating with nodes of the same side.

Attack#2: Routing attacks can delay block delivery

An attacker can use routing attacks to delay the delivery of a block to a victim node by 20 minutes while staying completely undetected. During this period the victim is unaware of the most recently mined block and the corresponding transactions. The impact of this attack varies depending on the victim. If the victim is a merchant, it is susceptible to double spending attacks. If it is a miner, the attack wastes its computational power. Finally, if the victim is a regular node, it is unable to contribute to the network by propagating the last version of the blockchain.

Attack scenario:

- Step 0: Nodes A and B advertise the same block to the victim, node C.

- Step 1: Node C requests the block via a GETDATA from node A. The attacker changes the content of the GETDATA such that it triggers the delivery of an older block from node A.

- Step 2: The older block is delivered.

- Step 3: Shortly before 20 minutes after the original block request made by node C, the attacker triggers its delivery by modifying another GETDATA message originated by C.

- Step 4: The block is delivered just before the 20 minutes timeout. The victim does not disconnect from node A.

The SABRE network can protect the Bitcoin system from partitioning attacks

To avoid partitioning the SABRE network needs to protect relay-to-relay connections and relay-to-client connections. To protect relay-to-relay connections SABRE places nodes in ISPs that peer directly to each other, forming a densely connected graph of direct peering links and also in /24 prefixes. To protect relay-to-client connections SABRE places relay nodes such that most clients have for each potential attacker at least one path to SABRE that is more economically preferred than any path this attacker can advertise.

Network Protection:

- SABRE design: SABRE is a small set of special Bitcoin clients that are directly connected to each other. Each Bitcoin client connects to at least one SABRE node.

- Step 1: An AS-level adversary isolates Bitcoin clients in the grey zone by hijacking prefixes pertaining to those clients, effectively creating a partition.

- Step 2-5: A block mined within the grey zone, namely by node n is propagated to the rest of the Bitcoin network via the SABRE relay network, namely nodes B, C, D.

The SABRE nodes can sustain DDoS attacks

As a publicly-facing and transparent network, SABRE is an obvious target for attackers who could, among others, craft (D)DoS attacks against its publicly-known nodes to disrupt it. To protect SABRE deployments against such attacks, we leverage the fact that most of the relay operations are communication-heavy (propagating information around) as opposed to being computation-heavy. In addition to that, the content (block) that the relays need to propagate each time is predictable and small in size. These properties enable us to offload most SABRE operations to hardware, using programmable network devices. Thanks to this software- hardware co-design, SABRE relay nodes can sustain up to Tbps of load.

Node Protection:

- SABRE design A SABRE node is a Software/Harware co-design that contains a control- and a data-plane component. The former is a Bitcoin client, extended such that it can update the memory of the switch with the latest Block. The latter is a programmable switch.

- Initial State: Bitcoin client are connected to the switch via UDP connections, while they keep their regular Bitcoin connections.

- Step 1: Node A mines a new Block.

- Step 2: Node A transmits the Block to node B.

- Step 3: Node B advertises the hash of the Block to the SABRE node.

- Step 4: The switch recognizes that the Block is unknown by performing a look-up on its memory. Since the switch cannot verify the Block, it allows node B to connect to the Controller directly via a Bitcoin connection.

- Step 5: The Controller validates the Block and updates the switch memory.

- Step 6: The switch propagates the new Block to all connected Bitcoin clients without the intervention of the Controller.

Publications

Hijacking Bitcoin: Routing Attacks on Cryptocurrencies

Maria Apostolaki, Aviv Zohar, Laurent Vanbever

IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy 2017. San Jose, CA , USA (May 2017).

As the most successful cryptocurrency to date, Bitcoin constitutes a target of choice for attackers. While many attack vectors have already been uncovered, one important vector has been left out though: attacking the currency via the Internet routing infrastructure itself. Indeed, by manipulating routing advertisements (BGP hijacks) or by naturally intercepting traffic, Autonomous Systems (ASes) can intercept and manipulate a large fraction of Bitcoin traffic. This paper presents the first taxonomy of routing attacks and their impact on Bitcoin, considering both small-scale attacks, targeting individual nodes, and large-scale attacks, targeting the network as a whole. While challenging, we show that two key properties make routing attacks practical: (i) the efficiency of routing manipulation; and (ii) the significant centralization of Bitcoin in terms of mining and routing. Specifically, we find that any network attacker can hijack few (<100) BGP prefixes to isolate ∼50% of the mining power—even when considering that mining pools are heavily multi-homed. We also show that on-path network attackers can considerably slow down block propagation by interfering with few key Bitcoin messages. We demonstrate the feasibility of each attack against the deployed Bitcoin software. We also quantify their effectiveness on the current Bitcoin topology using data collected from a Bitcoin supernode combined with BGP routing data. The potential damage to Bitcoin is worrying. By isolating parts of the network or delaying block propagation, attackers can cause a significant amount of mining power to be wasted, leading to revenue losses and enabling a wide range of exploits such as double spending. To prevent such effects in practice, we provide both short and long-term countermeasures, some of which can be deployed immediately.

SABRE: Protecting Bitcoin against Routing Attacks

Maria Apostolaki, Gian Marti, Jan Müller, Laurent Vanbever

NDSS Symposium 2019. San Diego, CA , USA (February 2019).

Nowadays Internet routing attacks remain practically effective as existing countermeasures either fail to provide

protection guarantees or are not easily deployable. Blockchain

systems are particularly vulnerable to such attacks as they rely on

Internet-wide communications to reach consensus. In particular,

Bitcoin—the most widely-used cryptocurrency—can be split in

half by any AS-level adversary using BGP hijacking. In this paper, we present SABRE, a secure and scalable

Bitcoin relay network which relays blocks worldwide through

a set of connections that are resilient to routing attacks. SABRE

runs alongside the existing peer-to-peer network and is easily

deployable. As a critical system, SABRE design is highly resilient

and can efficiently handle high bandwidth loads, including Denial

of Service attacks. We built SABRE around two key technical insights. First,

we leverage fundamental properties of inter-domain routing

(BGP) policies to host relay nodes: (i) in networks that are

inherently protected against routing attacks; and (ii) on paths

that are economically-preferred by the majority of Bitcoin clients.

These properties are generic and can be used to protect other

Blockchain-based systems. Second, we leverage the fact that

relaying blocks is communication-heavy, not computation-heavy.

This enables us to offload most of the relay operations to

programmable network hardware (using the P4 programming

language). Thanks to this hardware/software co-design, SABRE

nodes operate seamlessly under high load while mitigating the

effects of malicious clients. We present a complete implementation of SABRE together

with an extensive evaluation. Our results demonstrate that

SABRE is effective at securing Bitcoin against routing attacks,

even with deployments of as few as 6 nodes.

Presentations

Hijacking Bitcoin: Routing Attacks on Cryptocurrencies

IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy 2017. San Jose, CA , USA (May 2017).

SABRE: Protecting Bitcoin against Routing Attacks

NDSS Symposium 2019. San Diego, CA , USA (February 2019).

Code

- Prototype implementation of the delay attack.

- Bitcoin Network Testbed of 1000 bitcoind clients.

People

- Maria Apostolaki, ETH Zürich

- Gian Marti, ETH Zürich

- Jan Müller, ETH Zürich

- Aviv Zohar, Hebrew University,

- Laurent Vanbever, ETH Zürich, lvanbever ethz ch